ADVERTISE HERE

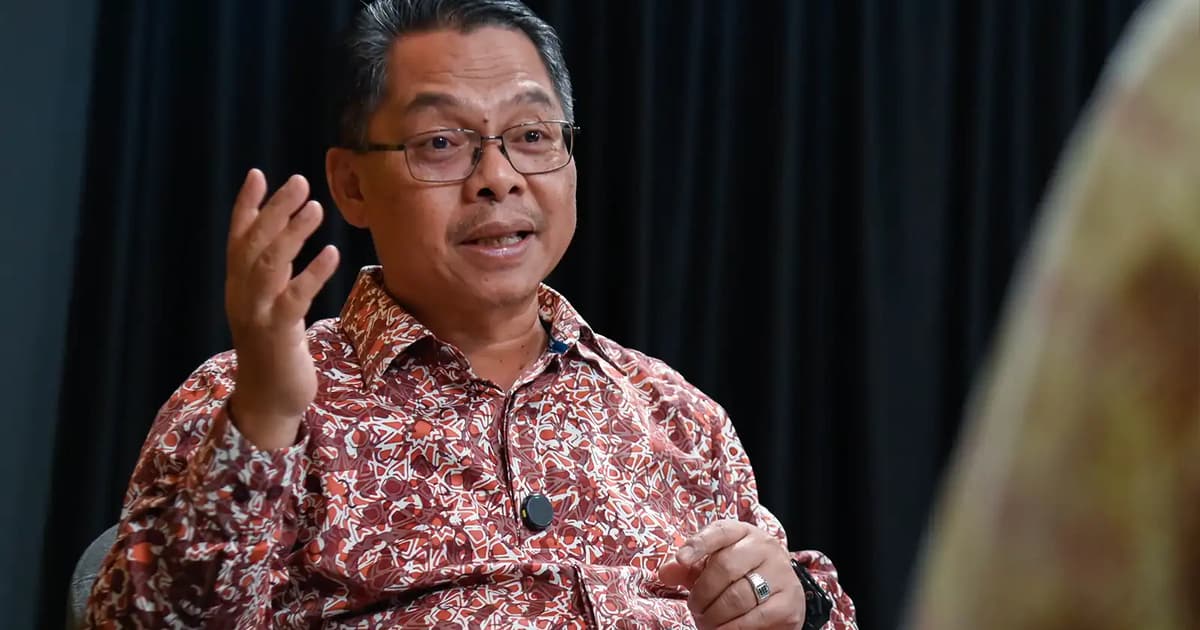

Photo for illustration purposes only. — Photo by Khairul Azizi/Pexels

IT is embarrassing that the problem of stunting in our children has to be highlighted by international data organisations—the recent tweet by Our World in Data (see image)—before it can gain more attention locally.

The fact that stunting has worsened in children in Malaysia has been known for the past 15-20 years. We have had good national data from the National Health and Morbidity Surveys (NHMS) to show that stunting in children under five years has increased from 16.6 per cent in 2011 to 21.8 per cent in 2022.

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently estimates that the stunting rate of children in Malaysia has increased to 24 per cent.

Stunting rates in much of the world are coming down but ours is worsening. Countries poorer than us—Laos, Cambodia, Bangladesh—are doing better with a decline in stunting rates. We have now reached a childhood stunting rate close to that of Bangladesh. As a comparison, the 2024 childhood stunting rates in Singapore and South Korea were < 3 per cent.

Why does stunting happen?

The majority reasons for stunting in our children are due to food security issues — lack of adequate nutrition in childhood as well as nutrition issues in pregnancy. Stunting is not something that happens just after you are born, it often happens before you are born. The NHMS 2022 data shows that 39.4 per cent of pregnant women were anaemic—a sign of nutrition issues and a major risk for low birth weight and stunting in the newborn.

Data shows that stunting was higher in Sarawak and Sabah natives, and those with household incomes of less than RM 1,000. Due to a lack of disaggregated data, we do not see that Orang Asli children have stunting rates of between 60 per cent and 70 per cent. We have no meaningful data on stunting rates for children in detention, refugees, stateless, and migrants.

All this points to poverty as a major factor for stunting. More than 1.2 million children are living in poverty in our country.

In addition, we have many children who are eating enough calories to feel full, but are lacking the essential nutrients—protein, iron, calcium, and Vitamin D—required for brain and height growth. Recent findings from the South East Asian Nutrition Surveys (Seanuts) II and NHMS 2024 highlight that 50 per cent of Malaysian children do not eat a diverse diet, lacking sufficient intake of fruits, vegetables, and dairy. The ubiquity of cheap, processed, and sugar-laden foods has created an environment for malnutrition.

Have we taken any action in the past?

We had a ‘National Children’s Policy’ and the ‘National Children’s Action Plan’ 2009-2015. In 2018 the government developed a ‘National Children Well-Being Roadmap (NCWR)’ to address the malnutrition issue but we are unaware of its impact. In the recently launched ‘National Children’s Policy and Action Plan’ the government has planned to address “the double burden of malnutrition among children and pregnant mothers” under Strategic Priority 3 (2026-2030).

There have not been any published, evidence-based data on the effectiveness of these policies and plans. I am not aware whether an independent external audit was conducted. The fact that our stunting rates have worsened is a clear indication that these plans have not worked. All government policies require an external audit as to their effectiveness, especially if they have not achieved their targets.

Remember, stunting is not primarily a medical problem or a failure of parenting. It is a failure of the many governments we have had in the past 20 years to act effectively in the face of good, national data showing that the problem has worsened.

What will it take for the government to declare this as an emergency and act?

There does not appear to be a national sense of urgency to resolve the crisis. Right now one in four children is stunted. The implications of this are staggering. The most tragic aspect of this crisis is its permanence—a window that closes forever.

Stunting indicates a permanent effect of malnutrition, which means the child will not be able to attain the potential adult height. Stunting also implies smaller brains and potentially poorer cognitive development, reduced productivity and this means a life time poverty trap. There is also data to show an increased risk of adult obesity, childhood infections, premature deaths and increased risk of stunting in the next generation.

What do we hope the government will do?

We cannot continue with ‘business as usual’. The fact that past plans have failed means that current plans may not work. We must address the lack of accountability of the government ministries and agencies tasked with stunting prevention. We need to have an urgent, external audit of plans and programmes to address malnutrition implemented in the past 20 years.

The critical window for preventing stunting is the first 1,000 days—from conception to a child’s second birthday—this must be our focus. A key to reducing stunting in children are structural reforms — to work on poverty reduction.

We need to commit to ending child poverty and malnutrition (achieving SDG Goals 1 & 2), especially in targeted groups—indigenous, rural Sabah, inner city, stateless, refugees. We need to focus on social determinants of health. We should use disaggregate, health determinants data—by income, location, ethnicity, etc—to identify those with inequities and target support for them.

If we are serious in dealing with stunting in our children, we need a national committee that has all stakeholders, is bipartisan, has strong civil society involvement, and is chaired by the Prime Minister.

Stunting steals a child’s future possibilities before they even have a chance to realise them. We cannot afford to let another generation grow up in the shadow of what they could have been. The impact of a 24 per cent childhood stunting rate will harm the nation for decades into the future.

Datuk Dr Amar-Singh HSS is a consultant paediatrician and child-disability activist.

The views expressed by the writer do not necessarily reflect the official position of The Borneo Post.

13 hours ago

8

13 hours ago

8

English (US) ·

English (US) ·